COLOMBIA’S WEAPONIZED COURTS: THE DAS WIRETAP SCANDAL THAT WASN’T

The use of false witnesses in Colombia is well-established. A number of high-profile cases have resulted in unfair convictions and in judgements against the Colombian state by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights

Colombia’s Weaponized Courts: The DAS Wiretap Scandal That Wasn’t

The use of false witnesses in Colombia is well-established. A number of high-profile cases have resulted in unfair convictions and in judgements against the Colombian state by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights

By Lia Fowler

October 07, 2017

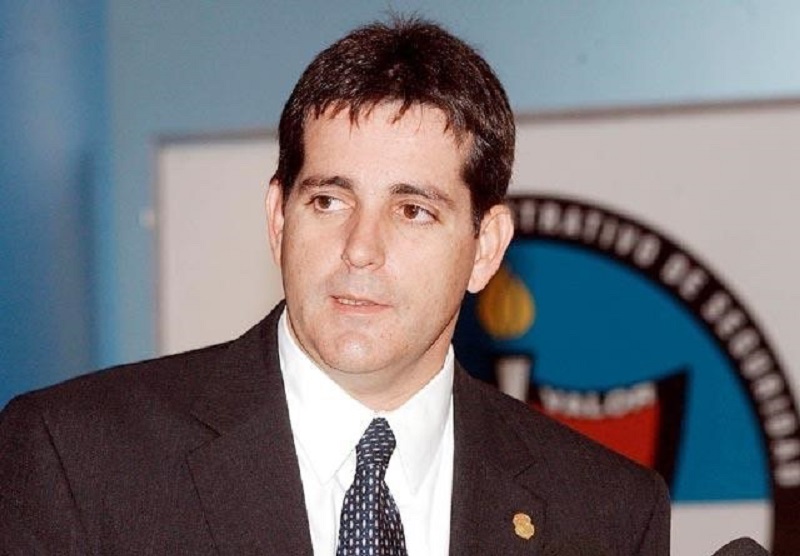

Jorge Noguera, former Director of Colombia’s now-defunct Administrative Department of Security, known as DAS, was convicted by Colombia’s Supreme Court this month of leading a criminal conspiracy that allegedly wiretapped political opponents of then-President Alvaro Uribe’s Administration. In its ruling, the Court further demanded an investigation into Uribe’s role in the conspiracy. But a review of the evidence, the Court’s arguments, and the timing and publicity surrounding the decision suggest it is more likely the embattled Court, and not Mr. Noguera, that is using its judicial power to persecute its political adversaries and shield itself and its cronies from scrutiny.

In the ruling, Magistrate Luis Guillermo Salazar Otero said Mr. Noguera led a group of DAS personnel, known informally as the G-3, “which, under the guise of carrying out strategic intelligence tasks, intercepted private communications with the agency’s equipment and conducted passive monitoring and financial investigations against the law.” Further, the Court found the objectives of the group were illegitimate, thus criminalizing all of its intelligence-gathering activities.

Yet prosecutors did not present a single piece of credible evidence to support the existence of any illegal phone or email interceptions. In fact, key exculpatory evidence provided by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration to investigators of the Inspector General’s and the Attorney General’s offices was not considered by the Court or made available to the defense. Further, there was ample evidence that the intelligence-gathering activities conducted by the DAS were well-founded and within the agency’s legal authority.

More than a dozen DAS executives, detectives and analysts have already served prison terms for these alleged offenses. But a fresh look at the evidence considered and discarded by the Courts as well as evidence concealed from defendants and logical leads ignored by the prosecution suggests the accused were victims of politically-motivated rulings that had little to do with justice. Now, with the conviction of Mr. Noguera, the Supreme Court – currently under scrutiny by U.S. authorities for selling verdicts — has opened the door for bringing charges against its ultimate target: Alvaro Uribe.

Background. What came to be known as “the wiretap scandal” started with a news article in the weekly magazine Semana in February 2009. Citing unnamed sources, the article alleged that the DAS had illegally intercepted telephone and email communications of hundreds of journalists, human rights activists, politicians, and even Supreme Court Magistrates critical of the Uribe administration. It added that in recent days, efforts had been made in the DAS to destroy the evidence. By April and May, the offices of the Inspector General and the Attorney General had opened administrative and criminal investigations into the article’s allegations.

While the investigation spanned the tenure of four separate DAS directors, Mr. Noguera was accountable only for activities during his term. Specifically, alleged illegal wiretaps against human rights Non-Governmental Organizations and journalists, chief among them the Corporacion Colectivo de Abogados Jose Alvear Retrepo (CCAJAR), between 2003 and 2005. As Mr. Noguera reported directly to the President, Colombian law required that he be tried in a single proceeding, before the Supreme Court, with the Magistrates acting as the jury, and with no possibility of an appeal.

Eight years later, on Monday, Sept. 11, 2017, news of the Court’s verdict against Mr. Noguera and the investigation into Mr. Uribe made headlines and dominated the news cycle. By then, of the nine magistrates that convicted Mr. Noguera, only five had heard the case from its inception. But a speedy trial and the benefits it offers the accused are of no concern to the Court. And despite some new exculpatory evedence found in these eight years, the Court relied on the same evidence that formed the basis of the Inspector General’s ruling against Mr. Noguera back in 2010: a single dead witness and a pile of photocopies.

Lack of physical and forensic evidence. To convict Mr. Noguera, the prosecution would have had to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that DAS personnel did indeed intercept “private communications with the entity’s equipment” without a judicial order, as specified in the ruling. Then they would have had to prove Mr. Noguera knew about it. They failed to prove either.

In fact, while there was not a single piece of physical or forensic evidence to suggest interceptions existed – credible evidence suggested they didn’t.

From 2003-2005, the DAS’ only mechanism for intercepting telephone communications was through a system known as Esperanza, which routed intercepted calls from telephone service providers, through the main switch in the Attorney General’s office, to listening stations at DAS headquarters: the Sala Plata (Silver Room), run jointly with the British Embassy and used exclusively for narcotics investigations; and the Sala Vino (Burgundy Room), which began operating in 2005, and was run jointly with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

As Robert Moody, owner and senior analyst at Forensic Data Services, a US-based digital forensics and computer security firm, explained, if phones and emails had been intercepted, or if evidence of wiretaps had been deleted, there would have been ample forensic evidence to prove it.

“There are always artifacts [bits of data] that can be interpreted to determine if something occurred,” Dr. Moody explained. “If data is being routed through switches and routers, these devices collect information about what is being routed through them.” Esperanza’s switch at the Attorney General’s Office, then, would have had artifacts related to the interceptions.

“Once recorded, these communications would be stored on hard drives,” Dr. Moody continued. “An examination of the hard drives would tell us whether or not recordings were made.”

Furthermore, the system is set up with searchable databases that pull information from the telephone lines, Dr. Moody added. “An examination of the databases would determine whether [the interceptions] happened and whether information was deleted, if someone was looking to cover something up.”

Dr. Moody explained there would also be ample evidence to prove the existence of a wire interception at the service provider. “There would be evidence those lines were tapped, because [the service provider] would have had to enter evidence into the system that would indicate where to route the line.”

Despite all the information that could have been available to investigators, the only forensic examination conducted was of the servers and databases at the DAS — and it came up empty. A report by the National Police Criminal Investigations Division, dated December 28, 2009, revealed that a search of the DAS servers and databases found “no direct evidence related to the interception or illicit violation of communications or monitoring of any persons from 2003 to 2005.”

Regarding the allegation that email communications were intercepted, it would have been easy to verify this by examining information from the email carriers.

“The provider would have all this great information and artifacts that would let you know if an email account was being monitored somewhere else, if it were configured so copies of emails were sent somewhere, or if blind copies of emails were generated and sent to a different location,” Dr. Moody explained. “The server and the service provider have that information. The question is whether or not someone wants to go look for it.”

It seems nobody did, as no forensic examinations of the switches or the service providers were ever reported.

There was, then, no evidence to support the Court’s ruling that the interceptions occurred and no good faith effort made by prosecutors to gather the pertinent evidence. The Court’s finding that the interceptions were conducted with the DAS equipment was flat-out refuted by the evidence:

Regarding the alleged email interceptions, a certification from Pen Link, the U.S. company that provides the interception infrastructure to DAS, dated November 1, 2010, was clear: “Pen-Link … has not ever supported the DAS with email interception capabilities.”

Regarding the interception of telephone communications, a March 2, 2009, embassy cable (09BOGOTA688) from then-Ambassador William Brownfield to the Secretary of State and other U.S. offices revealed the Esperanza system was not and could not have possibly been used to conduct illegal interceptions without judicial orders:

“DEA officials confirmed that Colombian investigators entered a DAS facility that had been operated jointly with DEA, and that DEA has cooperated fully in the probe. Inspector General (Procuraduria) investigators entered on February 23, where they reviewed evidence and interviewed DAS officials. Those investigators lacked the technical expertise to analyze their findings. CTI technical investigators joined the investigations the following day. DEA and DAS officials helped the CTI investigators gather data on all lines monitored at the facility so CTI could establish that proper judicial orders existed for each number. DEA officials confirmed that all operations were carried out with proper orders … DEA and DAS personnel explained that, contrary to press accounts, it was physically impossible to independently target telephone lines from the site.”

The offices of the Attorney General and the Inspector General, then, had credible evidence that the interceptions did not take place. Yet, the information was not referenced by the Court or by the Inspector General in their rulings. Further, it was withheld from the defendants in both the criminal and administrative proceedings. According to Colombian law, failure to disclose exculpatory evidence would constitute the violation of due process and could be evidence of malicious prosecution – as it would be under U.S. law.

Calls to Supreme Court Magistrate Salazar Otero and the Court’s press office to inquire about the lack of physical evidence of interceptions and the information provided by the DEA went unanswered. But Alejandro Ordonez, who as Inspector General in 2010 conducted the administrative investigation into Mr. Noguera and eight other defendants for the same underlying actions, was contacted via email on Sept. 15, 17, and 22 of this year.

Asked if he had ever heard any recordings of the alleged interceptions or evaluated any forensic evidence that proved the existence of interceptions or of any attempt to conceal them, Mr. Ordonez declined to answer. Asked further if he was aware of any report by his Office’s investigators of the DEA’s findings and testimony, as documented in Ambassador Brownfield’s cable, Mr. Ordonez again declined to answer.

In response to both inquiries, Mr. Ordonez provided the following statement: “The disciplinary process did not pertain to telephonic interceptions, but instead to abuse of power for acting outside of the authority of intelligence functions, deviating from the national interest.”

That’s not true. In fact, Mr. Ordonez’ statement is contradicted by his own ruling. In the Oct. 1, 2010, document, signed by Ordonez himself, he summarized charges against Mr. Noguera, specifically for the “interception of telephone and email communications without a judicial order” (page 55) and then proceeded to find him guilty of that specific activity:

“The conduct attributed to Jorge Noguera Cotes in the charges against him was executed continually from February 24, 2004, until October 28, 2005… and it has been proven, according to the investigative activity conducted, that during that time said group existed, and that the activities of interception of communications and emails (first charge) and monitoring of certain citizens (second charge) were continuous and permanent.” (emphasis added)

Mr. Ordonez goes on to cite the specific penal codes he found Mr. Noguera to have infringed, including articles in the Code of Criminal Procedure regarding the interception of telephone communications and the right to privacy.

What is clear today, is that both the Inspector General in 2010, and the Supreme Court in 2017, had no basis to establish that Mr. Noguera allowed, directed, or participated in any illegal wire interceptions. Further, the forensic evidence that was recovered indicated the opposite: that the interceptions never existed. Finally, it appears that evidence from a credible source (the DEA) that would have disproved the charge was withheld from the defendants in the wiretap investigation.

So what did the Court – and the Inspector General – rely on to reach what seems, in light of the above, a predetermined conclusion? The answer, again, points to political persecution.

Documents. The Court and the Inspector General both placed significant evidentiary weight on “documents” provided by the prosecution. But irregularities in the collection of this evidence and in the documents themselves should have made them inadmissible in a court of law. In fact, the unusual circumstances surrounding the documents point more to a fabrication of evidence than to proof of the alleged crimes.

According to a Judicial Police memo dated April 3, 2009, the documents were located in the file room of the Office of Analysis at the DAS — some were in file folders and the rest were stuffed in 32 plastic bags. This raises serious questions. It is reasonable to assume that between 2003-2005, DAS employees weren’t working out of plastic bags. Investigators established that the person with sole control of the documents during that time period was DAS employee Fernando Ovalle. But though it would have been important to establish who had access to the evidence in the intervening years — and how the documents wound up stuffed in bags — the issue was never addressed.

Further, the collection of evidence requires certain steps be taken to maintain the integrity of the process: agents should have photographed the location and state in which the documents were found, logs should have been kept of every piece of evidence recovered and its exact location, and a clear chain-of-custody log should have been kept to guarantee nothing was added or taken from the files after they were collected. None of this was done.

More concerning still, according to Court records and the testimony of several defendants convicted of the alleged wiretaps, all the documents found were photocopies – not a single original document was recovered. This alone should have rendered the evidence inadmissible. Colombian law logically requires that forensic examinations be conducted only on original documents, and it’s impossible to prove the authenticity of a document without a forensic examination.

Because all the documents were photocopies, it was impossible to determine if any were fabricated, tampered with, or planted. Original documents can be analyzed to determine, through the type and condition of the paper, the ink used, and any relevant watermarks, whether a document corresponds to the date it bears. This would have been vital in determining whether documents dated from 2003-2005 were authentic or fabricated later. Comparing individual sheets in multi-page documents would have helped identify if any portion of a document had been substituted. Finally, signature authentications can only be conducted on originals.

In a legitimate Court, the burden would have been on the prosecution to prove the legitimacy of the documents. Not in Colombia. Instead, the prosecution, the Court, and the Inspector General relied on this questionable evidence both to establish the existence of interceptions – for which, as established above, there was no physical evidence — and Mr. Noguera’s participation in the conspiracy.

Photocopies presented by the prosecution included what appeared to be damning evidence, including requests for wire interceptions written by the above-referenced Mr. Ovalle, and summaries of allegedly intercepted calls. All of these could have been written at any time. Conspicuously missing, though, was the wealth of reports a real telephone interception would have generated, including system-generated, time-stamped logs of incoming and outgoing calls registering the exact times, dates, duration and cell tower information for each intercepted call – reports that would have been impossible to fabricate. If an interception actually took place, these logs should have been found.

The summaries and transcripts of the alleged interceptions were also missing a key element that would have been included in authentic documents: the name of the person summarizing the call and of anyone reviewing or editing it. The documents presented by the prosecution, then, do not appear to be the work of a professional, but rather of someone unfamiliar with the proper protocols.

Finally, the photocopies included some minutes of meetings allegedly attended by many of the people accused of the conspiracy. One in particular, referred to as “Minutes of Meeting No. 1,” was found by both the Court and the Inspector General to be the key piece of evidence to prove Mr. Noguera’s knowledge of illegal activities, as it was the only document recovered that specifically mentioned him.

According to the document, Mr. Noguera met with his senior staff and members of the so-called G-3 group in March of 2005. During the meeting, Jose Miguel Narvaez Martinez, an advisor to the DAS also convicted in the “wiretap” scandal, allegedly stated that, “due to the sensitivity of the information, it was not pertinent to leave anything in writing.”

Indeed, the theory of the crime presupposes that the most senior members of Colombia’s intelligence community memorialized their illegal activities in official minutes – including instructions not to leave anything in writing. Such an assumption would seem ludicrous. But there’s more:

Even without a forensic examination, a look at the document raises red flags. The six-page document consists of four and a half pages of text, followed by three signature lines on the bottom of the fifth page – all unsigned — and a sixth page containing six additional signature lines. The pages are not numbered, and the last page, which bears a single signature, does not seem to correspond to the rest of the pages, as it is in a different font and size.

Mr. Carlos Alberto Arzayuz Guerrero, whose signature is the only one that appears on the document, on the sixth page, challenged the legitimacy of the document, under oath, in testimony before the Supreme Court in a related proceeding.

Asked by then-Magistrate Alfredo Gomez Quintero whether the meeting ever took place, he responded simply, “No, Sir.” Pressed further, he affirmed, “I am disavowing it,” and added: “A person would have to be very … stupid to memorialize the execution of a series of very serious crimes in a DAS document.”

Mr. Arzayuz pointed out a number of additional irregularities within the document. Mr. Noguera’s title was incorrect; despite Mr. Noguera’s alleged participation in the meeting, his signature line was not included; the identification of the members of the meeting didn’t follow proper protocol; and Mr. Arzayuz’s signature, quite plainly, appears superimposed onto the paper.

“I’m not an expert in this field,” he stated. “But just by looking at it, at the way my signature is placed on it, it raises doubts about how it could have been superimposed on that document at some point.”

Indeed, that is immediately apparent. So, Mr. Arzayuz challenged this document and others as “to their authenticity, their legitimacy, their origin; the circumstances in time, method and place where they were crafted.”

None of these statements by Mr. Arzayuz were given any weight in Court.

Mr. Noguera also requested a forensic examination of the “The Minutes of Meeting No. 1” in the 2010 administrative investigation against him. According to the Inspector General, a forensic expert attempted to conduct the examination of the document, but the original was never found.

In a legitimate proceeding, this would have worked in favor of the defendant, as the investigative bodies – both the IG’s office and the criminal prosecutors — would not have been able to establish the authenticity of the document. Again, not in Colombia, where the concepts of presumption of innocent and burden of proof are consistently violated.

So it is that the Court and the Inspector General ignored the lack of physical evidence of interceptions by giving credibility to unsigned photocopies that could not be authenticated. And they ignored the irregularities in the photocopies by giving credibility to a single witness: the above-mentioned Mr. Ovalle.

Witness Testimony. The investigation into the alleged wiretaps by DAS between 2003-2005 involved dozens of witness interviews. All but one denied illegally intercepting any telephone or email communication. All but one denied ever receiving an order from Mr. Noguera – or any other DAS official — to do anything illegal. All but one denied ever briefing Mr. Noguera about any illegal activity. Enter the star witness: Mr. Ovalle.

Mr. Ovalle was interviewed by the Attorney General’s office on several occasions between June and December, 2009, providing conflicting versions of events. Not only was he the only person to talk about wiretaps – of which there is no physical or digital proof — he was also the only person with access to the questionable photocopies.

But while Mr. Ovalle claimed that Mr. Noguera, senior and mid-level executives, and numerous analysts and investigators were involved in illegal wiretapping, he didn’t provide any specific information as to how the interceptions were performed or by whom. Further, he provided several conflicting accounts of who provided him with summaries and copies of the intercepted communications.

Mr. Ovalle died in January 2010, of pancreatic cancer. He never testified under oath and the defendants never had the opportunity to cross-examine him. In Colombia, as in the U.S., defendants have the right to confront their accusers. Mr. Ovalle’s statements, unsupported by any physical or forensic evidence and contradicted by every other witness, should have been thrown out.

Instead, violating every notion of due process, the Court and the Inspector General relied on Mr. Ovalle’s statements to “authenticate” the dubious photocopies and to overcome the lack of evidence. The failure by the prosecution to prove the existence of any interceptions, the exculpatory statements of the DEA, the questionable documents, the flaws in the chain-of-custody, and the wealth of exculpatory witness testimony all provided the reasonable doubt that should have resulted in the acquittal of Mr. Noguera and all those accused. But, as often is the case in Colombia’s politically-motivated prosecutions, it all came down to the word of a single person.

The use of false witnesses in Colombia is well-established. A number of high-profile cases have resulted in unfair convictions and in judgements against the Colombian state by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. In two of the most egregious cases, the NGO that represented, prepared, and presented these false witnesses before Colombian and international courts was precisely the main alleged “victim” in Mr. Noguera’s case: the Corporacion Colectivo de Abogados Jose Alvear Restrepo (CCAJAR).

The “Victims”. The CCAJAR is well-versed in the matter of false witnesses. Founded in 1980, it claims to be an NGO devoted to promoting human rights and social justice. But since at least 2002, the CCAJAR’s links to the narco-terrorist group FARC were known to Colombia’s Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) – an organization comprised of the chief of intelligence of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the directors of intelligence of the Army, Navy, Air Force, National Police and DAS, tasked with conducting strategic intelligence analysis at a national level.

Indeed, the CCAJAR has a history of promoting the FARC’s objectives and propaganda both at home and abroad. Among the FARC’s objectives is the weakening of the institution that most successfully combated them, the Colombian Military. Under the guise of representing victims of human rights abuses, CCAJAR has helped advance that goal by dealing significant blows to the national and international image of the military and the Colombian state, through judicial persecutions of high-profile members of the military – often with testimony from false witnesses.

The two most notorious cases involving false witnesses presented by CCAJAR involve alleged “forced disappearances” during the takeover of the Palace of Justice by the M-19 terrorist group in 1985, and the alleged massacre at Mapiripan in 1997.

In the first case, CCAJAR represented victims who claimed the Army had “disappeared” their relatives. Their testimony led to the conviction of Colonel Alfonso Plazas Vega and to a ruling by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights against the Colombian State. Col. Plazas spent eight years in jail before being absolved in 2015, after evidence was found that disproved the witnesses’ allegations.

In the Mapiripan case, the CCAJAR presented witnesses in Colombian and international courts that claimed their relatives were murdered in the massacre. These witness testimonies earned Colombia another conviction by the IACHR in 2005, and helped convict General Jaime Uscategui to 40 years in jail in 2009. By 2017, however, seven of these witnesses had confessed to providing false testimony.

But though the false witnesses in the latter case were convicted for their crimes, the CCAJAR has never even been investigated for its role in suborning perjury. It’s easy to guess why. After all, the DAS, Colombia’s premier intelligence agency, charged with conducting national criminal investigations, intelligence, border patrol, and protection, was dismantled and its staff persecuted and incarcerated, based on the non-sworn testimony of a lone, dead witness and some questionable evidence – all for having the temerity to conduct a legal intelligence investigation of the CCAJAR and their cronies.

On Intelligence. The accused in the wiretap scandal never denied collecting lawful intelligence on the CCAJAR and other NGOs in order to establish their links to illegally-armed groups. The investigation, as established by shared intelligence provided by the JIC, was well-founded. The CCAJAR’s links to the FARC were known to the entire intelligence community. The CCAJAR’s participation in forums of international organizations to which the FARC and other terrorists groups belonged was also well-established. And the identity of the CCAJAR’s President, Alirio Uribe, added to the legitimacy of the DAS’ intelligence-gathering.

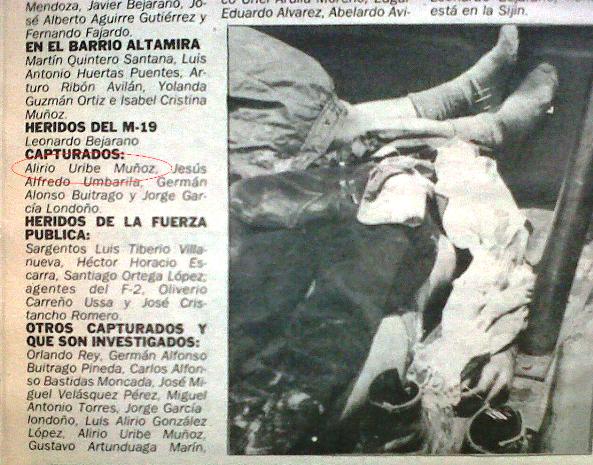

Press reports from September 1985, identify Alirio Uribe as having been arrested by authorities who responded to a terrorist heist conducted by the M-19, in Bogota – just a month before the atrocities at the Palace of Justice. Per press reports, Alirio Uribe and the other terrorists used human shields to shoot and launch grenades at law enforcement, resulting in the death of 11 people. Really, with this wealth of information, the question would be, what competent intelligence agency wouldn’t keep tabs on an organization with this profile and history?

Further, it was lawful and routine in Colombia –as it is in the U.S. — for intelligence agencies to collect information about a legitimate target through open source searches, attendance at public events, review of publications and broadcasts, and searches of national databases, without judicial orders. It was also lawful to analyze the information in order to indentify national and international threats to Colombia’s security and establish intelligence and investigative priorities.

That is exactly what the DAS did.

That’s called “strategic intelligence,” defined by the U.S. Pentagon as, “Intelligence that is required for the formulation of strategy, policy, and military plans and operations at national and theater levels.” It is done by every intelligence agency in the world.

But throughout the Supreme Court ruling, there is an effort to delegitimize strategic intelligence, referring repeatedly to “so-called strategic intelligence” — as if it were a concept made-up by Mr. Noguera as an excuse to “conspire.” The ruling also condemns the language used by the DAS to refer to the subjects of inquiry referring to “the ill-named targets or objectives,” despite the fact that this is language used across the field.

Much emphasis is placed on the fact that the group of people who worked on this intelligence task was not formed officially, but informally, claiming this made the group “clandestine.” This shows either ignorance as to regular operations within intelligence and law enforcement agencies, or a willful disregard for the truth. Any member of the intelligence and law-enforcement community would agree that it is normal for staff to create informal working groups to address specific administrative requirements (such as audits), major incidents (such as terrorist acts), or specific intelligence needs. Despite the Court’s ruling that the existence of the “group” was in itself illegal, it is appropriate for people in different departments to work together on a common task, as long as they don’t commit any illegalities. As we have demonstrated, there is no evidence to suggest that they did.

Finally, the press, the Court, and the Inspector General’s Office placed a lot of emphasis on the name of the group: The “G-3” plays well in the imagination of the public. But witness interviews indicate that, while the rank and file were familiar with the name by which some referred to the group, the executive staff was not. This is again indicative of law-enforcement and intelligence culture, and not of some nefarious conspiracy. As there was no G-1 or G-2 group in the DAS, the G-3 moniker was more likely a cheeky nickname made up by investigators and analysts in response to Cuba’s infamous G-2 intelligence agency, which, as it happens, was also a legitimate target of the DAS’ intelligence gathering. In any case, nicknaming a group of people working on a task is hardly illegal or proof of criminal intent.

Still, the Court ruled that the entire operation was a “criminal organization,” in essence criminalizing legitimate intelligence-gathering by the State. And it went further, placing CCAJAR and the other targets above the law and beyond investigative reach, as summarized in this passage: “…there is no doubt that they were part of the strategic intelligence and of the G-3 group, created to be permanent in nature, for the interception of telephones, emails and faxes without a judicial order and monitoring of people who did not conduct or to whom any illicit activity could be attributed…”

This conclusion, as we have demonstrated, is entirely flawed. Not only was there no evidence to prove that the DAS committed any of those illegal interceptions, there was a reasonable belief that CCAJAR and other groups monitored did indeed have ties with terrorists and illegally-armed groups.

And while the Court ruled that this was done because of the so-called victims’ opposition to the ruling party, it was the fabrication of “the wiretap scandal” that seems to have been politically-motivated by opponents — not only of Mr. Uribe’s government — but of Colombia’s institutions and system of government.

Indeed the “wiretap scandal” led to the closing of the DAS, and with it, the loss of vital human sources, trained and knowledgeable agents and analysts, and a wealth of raw and finished intelligence. Whether by accident or design, the Attorney General’s investigation and the rulings by Colombia’s courts achieved a very important FARC objective: the complete dismantlement of the State’s intelligence capabilities, the most useful tool in combating terrorism.

The Court. There is no denying the corrupt nature of Colombia’s Supreme Court. Indeed, in a 2009 recording of Magistrate Leonidas Bustos, released to the media in 2015, he stated: “… the arguments we make should be arguments of political convenience… If we try to validate this decision with arguments of a legal nature, this discussion would be Byzantine.”

Certainly, the decision to convict Mr. Noguera for political reasons would have been less “byzantine” and easier to come to than through a thorough and impartial review of technical and forensic evidence and informed deliberations about national intelligence – easier, convenient… and corrupt.

While Mr. Bustos is no longer on the Court, he was there when the case was being heard, through 2016. Also on the Court, since 2012, is Gustavo Enrique Malo Fernandez. Both of these magistrates are currently under investigation for corruption. The case against them was not initiated by Colombian authorities, as the magistrates have always been untouchable, but by a DEA investigation. Bustos, Malo, and another former President of the Court, Francisco Ricaurte – who was particularly vocal in condemning the DAS in the past – are being investigated for being part of a network of judges and lawyers who extorted millions of pesos from victims in exchange for favorable judgements.

Coincidentally, the DEA’s cooperating witness in the wiretap investigation against the magistrates happens to be Alejandro Lyons, the attorney to the “star witness.” Mr. Ovalle, in the persecution of Mr. Noguera and his staff. Mr. Lyons himself is accused of public corruption. According to press reports, Mr. Lyons has agreed to serve five years in jail in Colombia, in exchange for his testimony against others. Innocent and guilty alike should be leary of Mr. Lyons’ testimony, as the pattern of false witnesses and judicial persecutions seems poised to repeat itself.

vivian Morales and her husband Carlos Alonso Lucio, former guerrilla of the M19

Mr. Noguera knew in 2011 what many are coming to learn today: that Colombia’s Attorney General investigations and Supreme Court decisions have nothing to do with justice or the law. That year, Mr. Noguera was convicted of being part of a criminal conspiracy with paramilitaries and sentenced to 25 years in jail. Just as in the wiretap case, the Court relied on the questionable and contradictory testimony of a known felon and not a shred of direct or physical evidence.

So it was that on September 25, 2011, Mr. Noguera wrote a letter to then-Attorney General Viviane Morales, stating, “The irregularities in the treatment I received from these agencies, and the unjust conviction against me, have forced me to make the decision to disavow the authority of the Attorney General’s Office to investigate me, and of the Criminal Division of the Supreme Court to judge me in any case before them.” (See the letter to Morales here: Jorge noguera renuncia fiscalia)

Mr. Noguera never participated in any judicial proceedings against him again, and declined any representation by Court-appointed attorneys, deciding instead to appeal to International Courts for justice. After a thorough recitation of the violations of due process and the decisions that can only be construed as being politically-motivated, Mr. Noguera concluded, “With this aberrant sentence you will have robbed me of some freedom, but not of a second of peace.”

When Mr. Noguera was convicted of the first charge, in 2011, ex-President Uribe stated in his twitter account: “I appointed Jorge Noguera based on his resume and his family. I have trusted him. If he committed crimes, it hurts me. I offer my apologies to the citizenry.”

But now that the Court is using the politically-motivated, baseless conviction of Mr. Noguera to go after the ex-President – unjustly — Mr. Uribe should reconsider that apology and address, instead, the persecution of the Attorney General’s Office and the Courts against Mr. Noguera and the DAS staff unjustly convicted for the 2003-2005 events.

________________________________

Mr. Noguera has been incarcerated for more than 10 years; and more than a dozen members of the DAS lost years of their lives serving sentences for illegal interceptions that were never proven, and for conducting lawful and vital intelligence. It is impossible to give them back their time or their freedom. But it is possible, at least, to remember them, and give them back their good name:

In honor of Jorge Noguera Cotes, Giancarlo Auque De Silvestri, Jose Miguel Narvaez Martinez, Enrique Alberto Ariza, Jaqueline Sandoval, Carlos Alberto Arzayuz,, Hugo Daney Ortiz, Jorge Rubiano, Martha Leal, Ignacio Moreno Tamayo, Eduardo Aya Castro, Fabio Duarte Traslavilla, German Villalba Chavez, Rodolfo Medina Aleman, Luz Marina Rodriguez, José Velásquez and Mario Orlando Ortiz.

Comentarios